Over a thousand years ago, while writing in one of his Satires, the Roman poet Juvenal posed a question that has been haunting humanity ever since. ‘Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?’ loosely translates to ‘Who will guard the guards?’. Over the centuries, policing structures, judicial systems, and regulatory agencies have developed to monitor corporate behavior, citizen behavior, and government actions. Even the NGO space is now subject to systems of checks and balances. But who monitors the monitors? Thanks in large part to advances in Internet and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and the advent of social media there is now a bona fide and effective answer finally emerging: We Do.

Public trust is becoming the social and business currency de jour, even more ubiquitously powerful than the heralded bitcoin and blockchain. (For a good background read pick up Clay Shirkey’s Here Comes Everybody or see his Ted talk on Cognitive Surplus). Public trust has always been lurking in the fields, market places, and town squares and would periodically erupt to toss out a kingdom, confront a police force, replace a regime, or send a company’s stock price to zero. But it was often not until the steel was sharpened and the torches ablaze that the tangible degradation of faith in an institution was confirmed to have disappeared. Now however, through the analysis of crowd sourced information and opinion, we can evaluate how the guards are perceived and offer solutions and adjustments of engagement before the cobblestones become wet with blood. Aided by social media monitoring tools and techniques taught in the Digital and Social Media class at KSU, this month’s blog will evaluate the engagement of the institution operating in one of the most sensitive global hot spots today, and that is the Independent Electoral and Boundary Commission (IEBC) in Kenya.

The IEBC is an apolitical regulatory agency created by the new Kenyan Constitution in 2011. It is so apolitical that none of the nine commissioners are even allowed to be members in a political party. It is more akin to a company with a single product: To deliver a free and fair election process. The IEBC, by some measures, has been very successful in the delivery of that product to the public. The presidential elections of 2013, though quite close, were largely free of the rape, burnings, deaths and forced displacement that haunted the country in 2008. The 2017 elections were initially more worrisome, with such leading indicators as machete sales spiking through the roof (the nation has been successful in keeping firearm ownership quite low.) The August 8th elections were at the outset orderly, but multiple claims of fraud emerged in the aftermath, and there was sporadic violence. An apparently heavy handed police response resulted in scores of deaths, far below the thousand killed in 2008, but still each an individual tragedy. Then, the completely unexpected occurred.

For the first time in African history, a judiciary body stepped in and successfully nullified an election. The surprise ruling last week by the Kenyan Supreme Court was critical of certain aspects of the process and ordered the IEBC to construct a redo by November 1. The ability of the IEBC to rapidly conduct such a runoff is largely a function of the faith that the public has in the institution. Because of its apolitical nature, much of the discourse and engagement between the IEBC and the ‘customer’ takes place online. As Dr. Laura Beth Daws has noted before, these venues offer a plethora of free empirical data for the taking. TweetReach, by Union Metrics, was used to conduct a thorough analysis, not of the IEBC’s own feed, but of the marketplace use of the #IEBC hashtag. One hundred tweets over a recent 15 hour period were depicted. What kind of users were citing it? Influencers, bots, or ordinary citizens? What was the tone of the customers? Is IEBC perceived as part of the solution or part of the problem? This report starts to answer those questions and more:

Note that there is a healthy mix of contributor type. 22 of the 100 tweets were sent by users with over 10,000 followers. That is representative that some prominent influencers were citing the organization. 45 of the 100 were sent by users with between 1000 and 10,000 followers. This is an important group since it more likely represents non-institutional, authentic voices with a respectable genuine following. 33 of the 100 were sent by users with less than 100 followers. For context, there are 38 million mobile phone subscriptions in Kenya, representing 87% of the total population of 44 million. To have a third of the tweets citing the IEBC hashtag to have come from newer Twitter users with undeveloped following momentum is actually quite healthy and adds more credibility to the content analysis. All of this is a long way of saying that this was a good mix of origination type.

The content and tone reflected the diversity of the contributors. There was speculation of tension between some of the IEBC commissioners. There were worries that the computer systems may have been compromised. There was an ask for the IEBC to defend itself and speak to the hacking rumors. There was a call for one or more of the commissioners to resign. In some tweets there was empathy shown for the critical but thankless position of the regulator, with one poster calling the IEBC a career graveyard. Many others noted that the Supreme Court did implicitly voice confidence in the IEBC by calling upon them to run the process again. A few others (as well as some NGOs) pointed out that this ruling is actually a sound affirmation of the rule of law and the balance of powers in one of Africa’s growing democracies.

To develop further the recommendations for IEBC’s engagement, a triangulation with their Facebook activity is helpful. Likealyzer is a tool that ranks an organization’s Facebook page from 1 to 100 for engagement. As you see below the IEBC website scored a 74. To put it in perspective, even the Facebook page for the Kenyan Rugby team scored higher at 75.

There are some important admonishments in this analysis that point out that the IEBC Facebook page is late or non-existent in responding to inquiries. A cultural profile is emerging that the organization believes that they are merely a determinator and then a disseminator of information, when trust is actually built via two way dialogue. Likealyzer called the page’s response rate ‘catastrophic.’ The engagement rate of 8% appears anemic but not surprising if it is a one way conversation. Does a reader respond back to a newspaper? The report did highlight that there were better reactions to posts that included images, especially posts between 6 and 9 pm GMT. The ‘likes’ also had exhibited impressive growth north of 40%, now reaching 200,000 for the page, so there was initially an underlying base of goodwill to be leveraged.

The report recommends more links implemented by IEBC to other pages and posts, which makes sense. There isn’t even current continuity between the IEBC’s own Facebook and Twitter pages. For instance, the Twitter feed was explicit in the denial of some of the crazier rumors such as physical fights inside the commision, but the Facebook page was not prominent in controlling messages and images. Crisis management inside any traditional corporation seeks to immediately mitigate brand damage. A more dynamic and engaging social media policy by the IEBC will help instill the confidence necessary in the organization for them to fulfill their judicially authorized duty of conducting a free and fair fresh presidential election.

One thing is for certain, the crowd will be monitoring the monitors for veracity!

Photo by NPR via image source

All photographic rights owned via iStock

All photographic rights owned via iStock

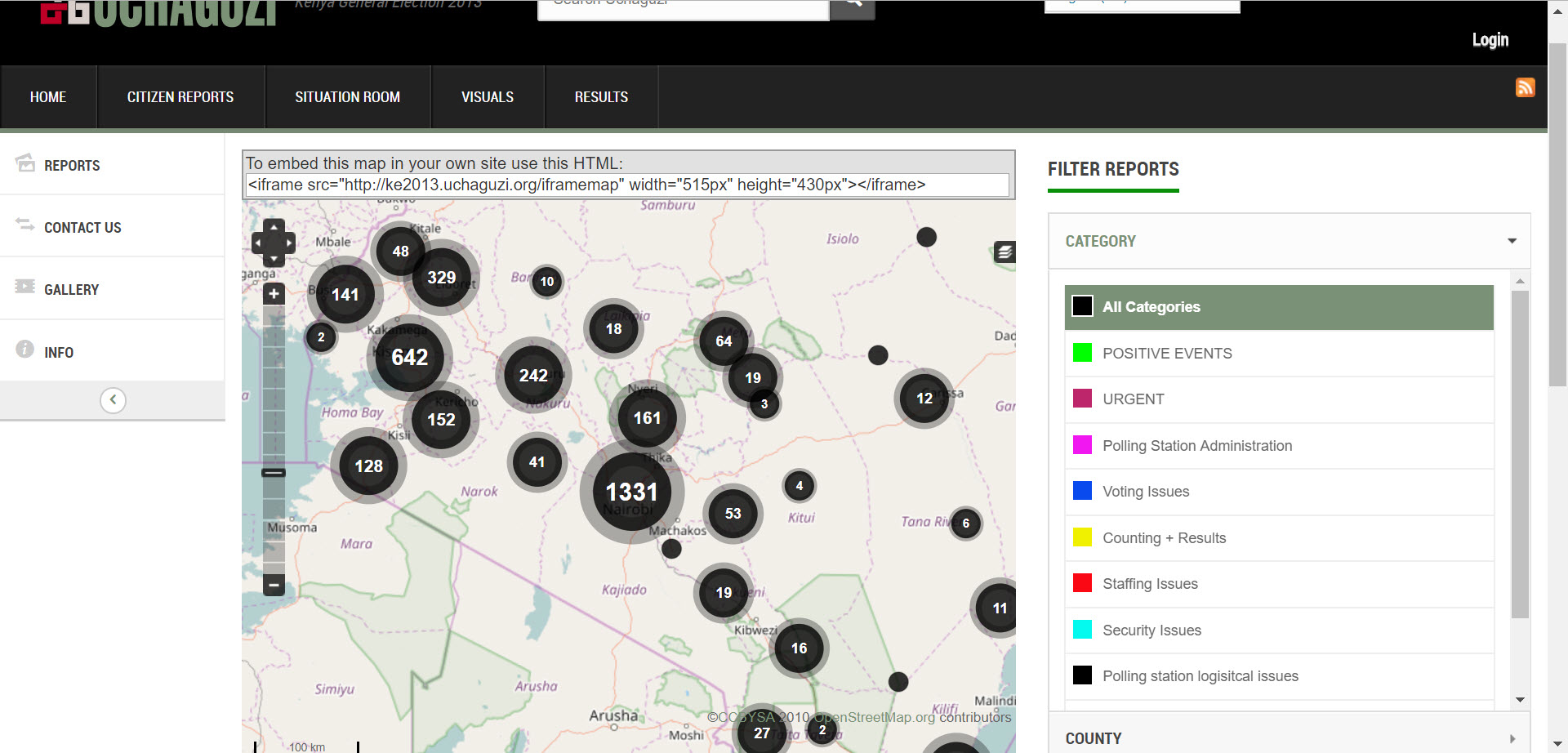

![IMG_5500[12201]](https://globalhumanitarianism.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/img_5500122011.png?w=685) I recently had the honor of serving on the Uchaguzi team for the elections that just concluded in Kenya. Uchaguzi is a mapping and events platform that runs on the Ushahidi (Swahili for ‘testimony’ or ‘evidence’) open sourced software system. It crowd sources input from the field via Twitter feeds, Facebook messenger links, and SMS in order to get a true picture of voting processes, inhibit election fraud, create an aura of oversight, and serve as a central repository for violence and security issues. Ushahidi was originally developed in the Kenyan 2008 deadly riots and has subsequently served in over a hundred governance, humanitarian, and crisis situations around the globe. This successful platform and other recent similar breakthroughs have given the capital of Kenya the nickname of the “Silicon Savannah.”

I recently had the honor of serving on the Uchaguzi team for the elections that just concluded in Kenya. Uchaguzi is a mapping and events platform that runs on the Ushahidi (Swahili for ‘testimony’ or ‘evidence’) open sourced software system. It crowd sources input from the field via Twitter feeds, Facebook messenger links, and SMS in order to get a true picture of voting processes, inhibit election fraud, create an aura of oversight, and serve as a central repository for violence and security issues. Ushahidi was originally developed in the Kenyan 2008 deadly riots and has subsequently served in over a hundred governance, humanitarian, and crisis situations around the globe. This successful platform and other recent similar breakthroughs have given the capital of Kenya the nickname of the “Silicon Savannah.”